A Life of joy and work

Recently I visited a park in my Kabul neighborhood—green space sealed behind concrete, barbed wire, and iron gates. Inside: the laughter of men and boys. Outside: women of all ages walking the dusty road, forbidden entry. I spotted schoolgirls carrying books, their seriousness throwing me back to my own youth. I was fortunate enough to build a career I loved, despite the obstacles. But I felt such sorrow for these girls, now banned from higher education and meaningful work. Afghanistan faces a darkness identical to the one I knew 30 years ago.

June 1992. I worked at National Radio and Television, papers in hand, preparing to record. The new television director—a mujahideen appointee—walked in, saw me, looked away in disgust. He told the producer he opposed women working. By refusing to look at me, he'd "shielded himself from sin."

I carried home a strange feeling. How could I work among people who viewed women with such loathing? Although I desperately needed the job, I resigned in fury. Soon after, most female employees were fired anyway. I never imagined that 30 years later, as I approach retirement, the situation for Afghan women would be far worse.

The mujahideen announced women must wear headscarves and cover completely. Many colleagues fled abroad. I lacked money to leave. I lost all income and labored under crushing poverty for two years. One day a former colleague hugged me on the street, then screamed when she touched my arm: "You're nothing but a skeleton! Thank God these clothes hide how thin you've become."

War stole our security, our jobs, our infrastructure. From our Kabul apartment, we walked long distances for water. Eventually our neighbors and I pooled money to drill a well ourselves. The government did nothing. I remembered a quote: "You don't have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great."

A decade earlier, after graduating top of my class in Languages and Literature, I'd secured my first teaching job. I taught literature at a boys' school in central Kabul. These weren't normal students—they were children of war, each with stories of horror. One fourth-grader, Gul Afghan, kept a photograph of his father, a pilot killed when insurgents shot down his plane. When a helicopter flew overhead releasing flares, he looked up mournfully: "If my father hadn't run out of flares, the enemy wouldn't have been able to shoot down his plane."

My job was to instill hope while struggling to hold onto my own. Soviet tanks drove past our school daily. I'd hold students' hands to walk them across the street, terrified a tank would run them over. Russian soldiers in steel helmets patrolled with Kalashnikovs, belts of bullets across their chests. My boys sometimes threw stones at them from a distance—their families had told them the Soviets were invaders.

I later became a lecturer, typing lecture notes and preparing classes for hours. Students held heated political debates—some backing the government, others the mujahideen. I had to remain neutral; there were spies even among students. The war took an emotional toll. I wished I could be a poet to express my feelings. Eventually I turned to fiction, finding peace in portraying people's lives.

Around this time I began working part-time at RTA, anchoring news and presenting literary shows. The building was guarded by Soviet soldiers and tanks. I'd arrive at 5 AM to start the day's broadcast. Although I wasn't affiliated with any party, I received death threats from the mujahideen for working with the government.

When the mujahideen gained control in 1992, fierce fighting erupted among them. One cold day after a rocket shattered our windows during heavy snow, I took my children to the balcony when the sun emerged. Below, boys gathered to play volleyball, their cheers filling the neighborhood. Then—a deafening boom. We fell to the floor. The rocket slammed into the volleyball field. The boys who'd been playing moments earlier lay motionless, covered in blood.

The next attack sent us to the basement. Eleven people died nearby, buried in a mass grave by the public staircase. Every day, trucks came as neighbors fled. Eventually only three families remained in our 40-apartment building.

I kept our savings, apartment deeds, and photos in a pouch around my neck, even while sleeping, ready to evacuate. After borrowing money from my sister, we attempted to escape with our two children. Twice we were turned back at checkpoints. Finally, with help, we found a driver who could get us to Pakistan.

Peshawar was another world: no fighting, no roadblocks, shops open. After recovering from the journey, I searched for work. Eventually I was hired by a media outlet to write for a literary magazine distributed in refugee camps. But we ached for home.

We listened to BBC and Voice of America every evening, hoping the war had ended. It hadn't. We endured Peshawar's heat, snakes, and insects. Though we had food and water, restlessness gnawed at us. Each evening, sadness swept our hearts.

After 9/11, the US-led invasion overthrew the Taliban. We could return. We found our Kabul apartment in ruins—blackened, windows broken, plumbing destroyed. We slept on the floor for weeks. Even with this hardship, life felt beautiful. Then one night an explosion shattered our window again—a bomb at a women's bakery. We wondered if we'd been too hasty, but had no choice.

In 2004 we voted in elections, high on democratic hopes, though corruption proved rife. Ironically, things improved dramatically for women—we could work and study again. I traveled the country gathering women's stories for radio plays: forced marriages, domestic violence, poverty, war. I met a 20-year-old forced to marry her cousin. "I tried to commit suicide," she said. "To this day I refuse to talk to my father." She was six months pregnant.

I hoped my plays would help women overcome their challenges. If they gave even a few girls courage to object to unwanted marriages, I'd consider that a great achievement.

After the Taliban regained control in August 2021, the clock rewound. My daughters sat their exams on the 15th; their usual short walk home took five hours. Waiting felt like eternity. Schools closed. Boys' schools eventually reopened. Girls' schools remain closed. My daughters were banned from university entrance exams. I felt their pain.

Women were forced into black hijabs, separated from male colleagues. In December 2022, we were effectively banned from working. I continued secretly from home, splashing cold water on my face at midnight when electricity finally came on, racing to finish before it cut out again.

It's been four years. Afghan girls are banned from education. Women can't enter parks, travel without male guardians, play sports, get driving licenses. Work is limited to healthcare and primary education.

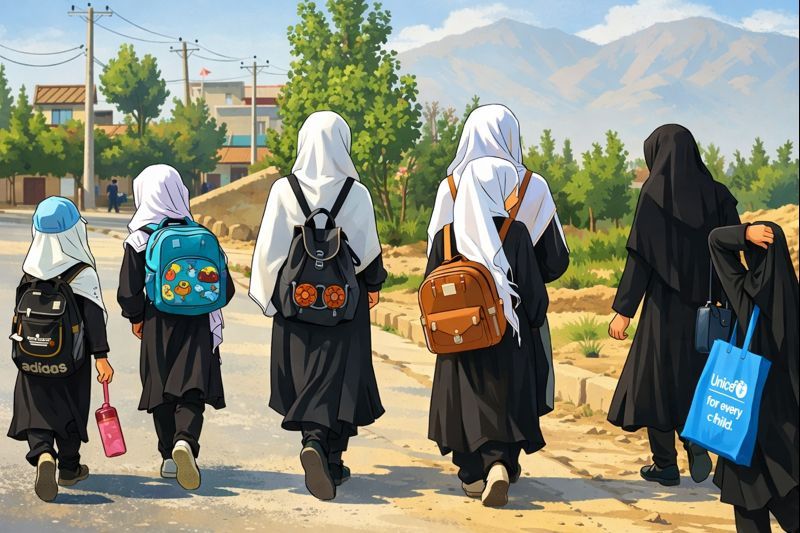

But there is hope. When I walk Kabul's streets, I see girls in black hijabs carrying backpacks full of books—determined to get educated by any means necessary. When I see the spring in their step and confidence in their stride, I envision a developed, prosperous Afghanistan under their leadership.